Piety and Forgery. The Problem of Pseudepigraphy in Late Antique Jewish and Christian Literature

by Lutz Greisiger

Pseudepigraphy is a phenomenon all but restricted to a certain culture or period like "Judaism and Christianity in Late Antiquity" in the title of this paper. There are two reasons why I chose this cultural sphere and this period - a minor one: it is more or less the field I'm about to specialize in; and a major one: it is the very field the vast majority of academic literature about pseudepigraphy is dealing with. Answering the question why the topic is discussed predominantly in this rather narrow cultural and historical range brings us immediately to the core of the problem.

Pseudepigraphic (from Greek pseud-epi-graphein) literally means "wrongly subscribed" or "wrongly ascribed". A text is called pseudepigraphic if it falsely states to be written by a wellknown author (or a mythical or historical hero). Pseudepigraphy is thus to be distinguished from pseudonymity - that is to circulate a text under the name of an invented, otherwise unknown, author, and from anonymity - that is to circulate a text without naming an author at all. [The two terms pseudepigraphy and pseudonymity are rather frequently used synonymously - which seems to me unefficient usage of terms resulting in blurred distinctions and confused concepts.]

The problem of wrongly or falsely asribed texts which are concerned authoritative is, I think, quite obvious. There are two main questions I want to point at:

1) How may the production of pseudepigraphic texts be justified - in other words: how could the author of such a fabricated text think that the claim for authority his text makes is legitimate?

2) How can such a huge amount of pseudepigraphic texts be considered authoritative, even sacred, although people are aware of the problem and, of course, reject forgery of such texts.

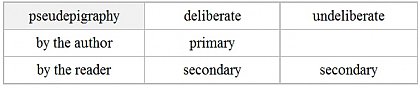

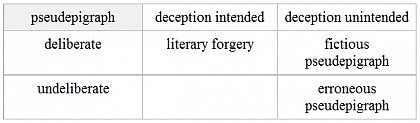

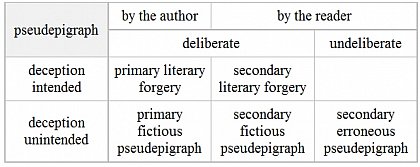

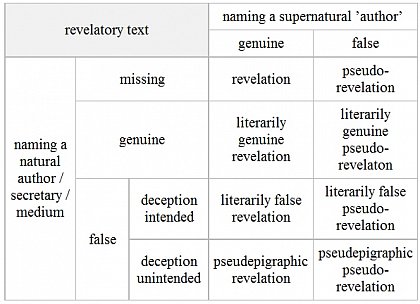

The following typology of pseudepigraphy is based on the work of Baum: "Pseudepigraphie und literarische Fälschung im frühen Christentum". I applied some minor changes, mainly to avoid the mistakable synonymous use of pseudepigraphic and pseudonymous.

Baum, resting largely upon his predecessors in the field of research of pseudepigraphy (but summarizing and systemising their results very clearly) makes three basic distinctions.

1) primary and secondary pseudepigraphy

If an author provides his work with another person’s name we can call this primary pseudepigraphy. This is the case, for instance, with the second letter to the Thessalonians, the letters to the Ephesians, Colossians, to Timothy and to Titus. These letters are ascribed by their so-called pre-scripts to the apostle Paul but have been actually composed by other authors who lived some time later.

We can speak of secondary pseudepigraphy when we are dealing with texts which are ascribed to the wrong author by their readers or by a certain tradition. We find an example in the four Gospels which circulated as anonymous texts and were later provided with the title "Gospel according to Matthew, Mark" and so on.

2) deliberate and undeliberate

Another basic distinction we have to make is that between deliberate and undeliberate pseudepigraphy. The author himself as well as the reader can ascribe a text deliberately to another person. So we can distinguish between primary and secondary deliberate pseudepigraphy. We will hardly find a case of primary undeliberate pseudepigraphy: writing under a false name is always knowingly and intentional. But there are numerous examples for secondary undeliberate, that is erroneous, pseudepigraphy. This is the case with the Apocalypse of John which has been actually written by a certain John of Patmos but has been ascribed by tradition to John, the son of Zebedee, one of the disciples of Jesus. Here the homonymity of two persons caused a wrong ascription which, by the way, is the reason why the Apocalypse of John, despite the strong reservations about apocalypticism held by the church, could become part of the biblical canon. Erroneous ascriptions can also be caused by anonymity (when a text is ascribed to a person because of its content or style), by mistakes of copyists and the like.

3) deception intended or unintended

Another distinction made by Baum is that of whether the wrong or false ascription is made with intent to deceive or not. In some cases the author reckons on his readers' ability to see through his falsification of authorship. This form of literary fiction seems to be restricted mainly to modern literary history. However it is to be found in antique literature too: Salvian of Marseille for instance circulated a work of his under the name of Timothy, the famous disciple of the apostle Paul. In a letter he stated that he did so not to deceive the audience but to refer symbolically to the Glory of God. In cases like this we can speak of fictious pseudepigraphy.

If one can assume that an author writes under the name of another with intention to deceive his readers, this can be considered as a literary forgery. Concerning the moral implications of the term forgery it is not surprising that the question if we can possibly impute fraudulent intent to the authors of, for instance, the above mentioned pseudo-Pauline letters, has puzzled generations of scholars. Furthermore it is little surprising that the majority of the scholars devoted to this question are theologists. The problem behind the academic discussion seems to be therefore nothing less than that of the authority of scripture. If the term forgery is at all appropriate in the context of Jewish-Christian writings is still a matter of a vigourous debate. Some positions concerning this questions will be sketched later on.

The same applies, at least to some extent, to secondary literary forgeries which occur if not the author himself but another person or group deliberately circulates texts under false names. Finally we can assume that in some cases also a secondary pseudepigraphy might be intended not to deceive the reader.

A good deal of the late antique literature - or literatures - in which pseudepigraphy occurs is, or has been, thought to be inspired by God. This dimension of the problem becomes crucial when it comes to revelatory texts in which we have to deal with two authors, a natural and a supernatural one. I don’t want to go through all the distinctive criteria employed by Baum. Let me just direct your attention to the fact that he doesn’t want to rule out the possibility of genuine revelation.

Allowance of this possibility in a terminological system makes sense (even outside theology) when applying another basic difference, namely that between the object-level and the metalevel. Modern literary criticism has made out a huge amount of texts of late antique Jewish and Christian literatures as pseudepigraphic. Its methodology and terminology apply to the meta-level of academic discourse. However when discussing the conditions of deriving, asserting and maintaining authority by texts in a certain period it is also necessary to look at the attitude towards pseudepigraphy which was adopted by the contemporaries - that is to discuss the notion of pseudepigraphy on the object-level. On the object level we also have to include not only the possibility but the real occurrance of revelation.

It has been argued by earlier philologists that the people in antiquity had had an underdeveloped sense of intellectual property; therefore the notion of forgery would merely be applicable to modern literature. [If the term "intellectual property" is of any use in the analysis of the phenomenon of pseudepigraphy seems to me rather doubtful.] However the ancients were aware of texts being wrongly or falsely ascribed to certain authors; even the term pseudepigraphon is of ancient origin. The earliest testimony of Greek criticism of genuineness is to be found in the works of Herodotus who expressed his doubts about the correct attribution of some of the Homeric writings. In the school of Aristotle this literary criticism was practised in a systematic manner. When, in the Hellenistic period, the famous libraries of Pergamon and Alexandria were founded, it was developed into a distinguished scholarly discipline. To ascertain the genuineness of a book several methods, criticism of form and style, chronological, linguistic, even paleographical criteria were employed. Once a text had been identified as pseudepigraphic its chances to survive decreased rapidly: no one would furthermore copy, buy or keep these books.

It has been stated, furthermore, by some scholars that the sense for the individual creative achievement had been underdeveloped in Jewish and, partly, Christian societies compared to the Greek culture. This is also arguable. In Rabbinic literature we find numerous statements which express the high regard for the correct attribution of a saying to the authoring Rabbi. The Christian Church Fathers adopted the techniques of non-Christian antique criticism. The early church faced a serious threat by the sheer multitude of texts ascribed to authorities like Paul, Peter, John, Thomas as well as characters of the Old Testament. To define the scope of Orthodox faith they strove to exclude beliefs considered as "heretic". Therefore the criterion of the orthodox or heretic content of a text became predominant. Another criterion was whether a recognised Apostolic church adopted a certain text as a source of faith. Extracanonical books, even if their content did not contradict to the "orthodox", had at least a dubious reputation.

Obviously the genuineness of a text was held in high esteem and forgery was refused in late antiquity. Why then pseudepigraphy seems to be the rule rather than the exception?

It has been argued that writing under a false name is not to be considered necessarily as an act of forgery - it could simply express the respect and the devotedness to a certain person. The author is aware that his own thoughts derive from an authority of the past. This is certainly the case in philosophers’ schools like that of the Pythagoreans. There are several pseudo- Pythagorean texts written by disciples of the great teacher. A similar case has been assumed for the circle in which the pseudo-Pauline letters were produced and which is frequently called the Pauline school. The importance of schools for the process of tradition is more than obvious in Rabbinic literature. One can assume that these schools produced a lot of pseudepigraphic material devoted to the great authorities. It has been shown that in Judaism tradition is always related dialectically to a process called in German "Vergegenwärtigung" which can be translated only inadequatly as actualization. Any newly produced literary material has to refer to the authoratative tradition thereby interpretating tradition to make it applicable to the present conditions. In a structure like this an athor is more likely to shy away from giving statements in his own right and to be inclined to attribute his work to an authority much greater than his. To make this attitude more plausible it seems to be useful to point at another difference: pseudepigraphy is the exact opposite of plagiarism. It seems that at least in some segments of late antique literary production plagiarism (that is to circulate texts and ideas from another person under one’s own name) was considered much more immoral than to attribute one’s own texts and ideas to a well-known authority.

Another point which has been made is that authorship is to be considered as part of the text itself. Some scholars have argued that there is a certain contract between the author and the reader. The latter ’reads’ the declaration of authorship as part of the message, a signal that indicates the tendency and dedication of a work. Furthermore post-modern criticism of the concept auf authorship in general has been applied to pseudepigraphy. These arguments shift the approach from production-aesthetic to reception-aesthetic which seems to be suitable for a good deal of cases of pseudepigraphy.

But it is one thing to attribute one’s own writings to natural and historical persons; it is quite another to fabricate the actual word of God. In the second century B.C.E., a time when prophecy was believed to have come to an end so that direct interaction of God with human beings would not occur anymore, certain Jewish circles began to produce apocalypses. Apocalypse literally means "revelation" and these texts describe such revelations allegedly received by biblical heroes like Henoch, Baruch, Ezra and the like. The themes of these revelations are cosmogony, cosmology and particularly history and eschatology. If one assumes that these texts are not forgeries in the strict sense but reflect real revelatory experiences of their writers - at least some portions, the so-called vaticinia ex eventu, prophecies of events which lie in the past but were allegedly foreseen by the hero of the apocalypse in his revelation, these portions stay "forgeries" of God’s word (or revelations transmitted through the medium of an angel).

To my view it is hard to imagine how a pious person in late antiquity could consider this practice as justifiable. It might seem easy to find explanations for most cases of pseudepigraphy. However, in the case of revelatory texts like apocalypses a satisfying explanation is still missing.

SPEYER, Wolfgang: Die literarische Fälschung im heidnischen und christlichen Altertum. Ein Versuch ihrer Deutung (Handbuch der Altertumswissenschaft I.2). München, 1971.

METZGER, Bruce: Literary Forgery and Canonical Pseudepigrapha. In: Journal of Biblical Literature 91, 1972, S. 3-24.

MEADE, David G.: Pseudonymity and Canon. An Investigation into the Relationship of Authorship and Authority in Jewish and Earliest Christian Tradition (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 39). Tübingen, 1986.

BREGMAN, Marc: Pseudepigraphy in Rabbinic Literature. In: CHAZON, Esther; STONE, Michael (ed.): Pseudepigraphic Perspectives: The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha in Light of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Proceedings of the International Symposium of the Orion Center for the Study of the Dead Sea Scrolls and Associated Literature, 12–14 January, 1997 (Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah 31). Leiden; Bosten; Köln, 1999, S. 27-41.

BAUM, Armin Daniel: Pseudepigraphie und literarische Fälschung im frühen Christentum (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 2. Reihe 138). Tübingen, 2001.

JANSSEN, Martina: Unter falschem Namen. Eine kritische Forschungsbilanz frühchristlicher Pseude- pigraphie (Arbeiten zur Religion und Geschichte des Urchristentums 14). Frankfurt a.M. u.a., 2003.