The Torah in Primitive Christianity

by Lutz Greisiger

Übersicht

Torah in Early Judaism

The basic characteristic of Judaism has been termed a "covenantal nomism" (Ed Parish Sanders). The term applies to a key issue of Judaism, namely its occupation with Law. The added adjective indicates that this Law, torah in Hebrew, is not the subject of a mere nomism or "legalism" as it has been labelled, thereby curtailing the notion of Torah and, what is more, updating one of the most long-living stereotypes of anti-Judaism. Therefore, in order to understand the notion of Torah correctly, deliberation has to be observed when talking about the Law in Judaism.

The meaning of torah in ancient Israel was "direction", or, "instruction", but, as early as the book of Deutoronomy (5. Moses, 7th cent. BCE) it referred to a collection of authoritative traditions in the form of a book. From post-exilic times (after 538 BCE) on torah meant the obligation revealed to Moses on Mount Sinai and mediated by him to the people of Israel. Since this Law was perceived as being codified in the 5 Books of Moses, the Pentateuch, the term torah also referred to these. The Pentateuch, however, is more than a mere law code – besides the law texts it contains narratives of the history of creation, of the Patriarchs, the Exodus from Egypt, the occupation of the Promised Land and the like. And the directions it contains comprehend areas, such as religious observance and moral behaviour, which fall outside the boundaries of law in a narrower sense. Observance of the Torah is therefore not only abiding the Law but a highly ethical demand.

Soon the entirety of scripture, like the other biblical as well as extracanonical books were considered as Torah, at least those who could be consulted to clarify passages of the Pentateuch, the interpretation of which were controversial or uncertain. Debates and opinions of the Rabbis about the correct implementation of regulations were collected, transmitted orally and later written down. These collections were revised and codified in a long process of which the results were the Mishnah (completed around 200 CE) and the two Talmudim (5th and 6th century CE respectively). These collections were referred to as Oral Torah, in distinction to the Written Torah of the Pentateuch. The oral tradition began in all probability already in biblical times and was conceived as going back to the revelation on Mount Sinai, thus being an integral part of the Torah as well. The regulations of the Torah are concerned with common prayers, personal worship, sabbath and feasts, the temple cult, purity and impurity, fasts, matrimonial law, civil and criminal law, court rules, regulations concerning the social and societal order like tax laws, social welfare, debts and debt relief etc.

By accepting the Torah Israel had entered a covenant with God. The Torah, Israel’s law, therefore is not to be considered in isolation from this covenant. By revealing His will to Israel God made her His chosen people. Thus the Torah is exactly what distinguishes Israel from all the other peoples. But the Israelites are not only privileged but profoundly and universally responsible by their possession of the Torah. Breaking the Law means breaking the covenant with God and therefore endangers Israel as a whole. Thus the individual observance is of grave relevance for the collective welfare. Moreover the Torah represents the order of God’s creation. Consequently on the one hand by the Torah Israel possesses the key to the very core of God’s creation which surpasses any human philosophy; on the other hand the well-being not only of Israel but of all mankind, even of the whole creation is seen as dependent of her obedience to it.

Torah is more than an order of life or a social order, it is not a mere legal or moral system – its implementation means God’s reign on earth and leads to human salvation.

Torah in the Preaching of Jesus

Throughout the Gospels we find numerous passages in which Jesus polemises against the (nowadays proverbial) Pharisees and scribes. This polemic refers to a literal obedience to the Law while avoiding to act according to its spirit. When e.g. the disciples were hungry and plucked ears of corn on a sabbath and they were rebuked by Pharisees because they had violated the commandment of the sabbath rest he answers them "The sabbath was made for man, and not man for the sabbath" (Mk 2,23). By their literal application of the Law they "you shut off the kingdom of heaven from people" (Mt 23,13). The Pharisees were a religious movement within Judaism from the 2nd century BCE to the first century CE the traditions of which (that what was later termed Oral Torah) were transmitted to the later Rabbinic movement. The scribes were learned men and experts of the Torah. What Jesus accuses the Pharisees and scribes for, in passages like those quoted before is exactly that "legalism" which still 19th and early 20th century scholarship ascribed to Judaism. With their demand of literal obedience to the Law the Pharisees here are denigrated to obstruct their followers’ way to salvation.

In other Gospel passages however Jesus seems to plead for the contrary: "The scribes and the Pharisees have seated themselves in the chair of Moses; therefore all that they tell you, do and observe, but do not do according to their deeds; for they say things and do not do them." (Mt 23,2–3) The theoretical authority of the Pharisees in questions concerning the Law and their interpretation of it is acknowledged; only morally they are to be criticized. And in another passage Jesus seems to controvert certain tendencies among his later followers as if he had foreseen them: "Do not think that I came to abolish the Law …; I did not come to abolish, but to fulfil." (Mt 5,17)

So Jesus had left his followers with quite contradictory statements concerning the crucial point of the relevance of the Law. This conflict was to become represented in the contesting currents or parties within the Jesus movement after His death.

Torah in the Jesus-Movement

Jesus’s preaching was addressed quite exclusively to Israel, his people; therefore his criticism of the Torah practise of the contemporaries can hardly be conceived as questioning the Torah as a basic principle. Furthermore the Gospels were composed several decades after Jesus’s lifetime and in the process of transmission the antinomistic tendencies of the traditions might have been strengthened. It can therefore be assumed that his actual position had been that which is documented in another sentence: "For truly I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not one jot or one tittle shall pass from the Law until all is accomplished." During Jesus’s lifetime and in the first years after the death of their Messiah his followers had no reason to doubt the validity of the Torah. He who had come humble and despised would soon return as the almighty redeemer. Until this event the community had their daily meetings in the temple praying and awaiting Him – and they observed the Law which, as He had explicitly declared, should not come to an end until the end of this world. The early followers were, apart from their conviction that the Messiah had come in Jesus of Nazareth, faithful ’Pharisees’.

Things began to change when tensions arose between the Jewish believers in the Messiah and another group of followers called the "Hellenists" within the community at Jerusalem. This group seems to have consisted of Greek speaking Jews (most likely originally coming from diaspora communities and later having settled in the city, including a number of proselytes of non-Jewish descent) who were opposed to the traditional authorities, their conception of Torah and the temple cult in Jerusalem. Soon their radicalism lead to a persecution by the Sanhedrin, the Jewish supreme court, and to the stoning of one of the Hellenists by the name of Stephen. The other Hellenists were expelled from the city and worked as itinerant preachers all over the land. At the same time the more traditionallyminded Jesus-followers were not the subject of persecution but were accepted as Jews among Jews and allowed to stay in Jerusalem. In the following, however, the authorities increased the pressure on the rest of the Jerusalem community as well, and one of the Apostles, James, son of Zebedee, was executed while Peter was temporarily imprisoned. James, the brother of Jesus became the head of the community. As "James the Just" he was widely famous among the Jews of the city for his piety and his allegiance to the Torah.

In the meantime the expelled Hellenists had propagated their new faith all over the Levant, even as far as Damascus and Cyprus. The most eminent community was founded in Antioch. The majority of new converts there came not from the Jews but from the God fearers. These gentile proselytes had adopted the Jewish faith with their code of morality and attended synagogue services, but were not full converts and did not want to submit to circumcision. They restricted themselves to certain leading points of the Torah and were regarded as outside the fellowship of Jewish communities. Now the relations between Jews and gentiles were handled quite differently within the Antioch community. Here on the gentiles no circumcision and no Law-observance was imposed while the two groups lived together and associated in a table fellowship which was quite precarious in terms of purity. This new community appeared as quite distinct from the Jews to outsiders and therefore soon was named christianoi, Christians. It was here that the new religion emerged and broke away from Judaism, its ’mother-religion’.

The ’Apostolic Council’

The ’headquarter’ in Jerusalem maintained close contact with the newly founded communities and it was only a matter of time before conflicts broke out between the two different communities of Jerusalem and Antioch. An emissary of the Jerusalem community, by the name of Barnabas, was sent to Antioch, who stayed there and appointed a certain Saulos from Tarsos, who bore the cognomen Paul, as his assistant. Both Barnabas and Paul came from Greek speaking Jewish diaspora communities. Paul had been educated in Jerusalem and his teacher had been the great Gamaliel, leader of the Pharisees and later recognised as one of the first rabbinic authorities. Paul later admitted to have been a zealous activist for the Law and to have been engaged in the persecutions of the Jesus-sect. After a vision of the resurrected Jesus he had not only converted to the new faith, but henceforth appointed himself Apostle, an office which usually was restricted to those followers who had accompanied Jesus personally. Paul on his part had not even met Jesus.

Now, in Antioch the smouldering conflict about the demand of circumcision and Law observance of the new gentile Christians broke out openly. Had for a long time individual proselytes naturally converted in full and had become Law-observant Jews, the rapidly growing majority of gentile Christians now did not accept the validity of the Law for themselves. In their attitude they found supporters among the Hellenists, most notably Barnabas and Paul. The two travelled, accompanied by the uncircumcised proselyte Titus, around the year 48 to Jerusalem to meet the "pillars" of the community (James, the brother of Jesus, Peter and John, the son of Zebedee) and to convince them that their way of a "Law-free mission" among the gentiles was right. The result of this so-called "Apostolic Council" was that the mission should be split into a Jewish, lead by the three "pillars" and a gentile one, represented by Paul and Barnabas.

Thereby the "Law-free mission" among the gentiles had been sanctioned, but this obviously did not solve the problem of the practical consequences for the co-existence of Jews and gentiles in so many Christian communities. The results of the "council" were published in a circular letter, also known as the "Apostolic Decree". According to this document a kind of ’minimum Torah’ should be imposed on gentile Christians (containing prohibition of extramarital sexual intercourse, meats offered to idols and unkosher slaughtered meats). These prohibitions are a version of the so-called "Noachite Laws", traditionally valid for non-Jews who lived amongst Jews, especially in the Holy Land. These regulations were chiefly meant to prevent the life style of the non-Jews from interfering with Jewish purity laws.

The Christians of Antioch further on did not care about purity Laws, and Jews and gentiles attended the common table fellowship. When Peter visited them he took part in their meals and only when conservative emissaries from Jerusalem arrived he separated himself from the uncircumcised, an attitude which caused some of the Jerusalemites to denounce him of acting against the compromise. Paul on the other hand blamed him of being inconsequent: "If you, being a Jew, live like the Gentiles and not like the Jews, how is it that you compel the Gentiles to live like Jews?" (Gal 2,14). On his missionary journeys Paul preached a consequently Law-free Christianity, time and again confronted by conservative Jewish Christians who continued to insist on circumcision and Law observance also for gentile Christians.

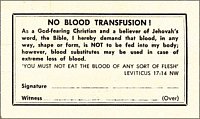

Christian Torah-observance in the 20th century: no blood transfusion statement to be carried by ’God fearing’ Jehovah’s Witnesses (www.ajwrb.org/watchtower/card.shtml).

From these controversies at least 3 ’parties’ within early Christianity emerged: one strictly Jewish-Christian group which insisted on the full Torah observance for all Christians, one moderate whose position was represented by the Apostolic Decree, lead by Peter and James and one strictly antinomistic group lead by Paul. Since the strict Jewish Christians soon lost its influence on the early Church, their fate can be ignored here. The traditions of the Church originated in the moderate Jewish Christian and the Pauline currents within primitive Christianity and the Jewish element decreased rapidly after the first century.

The ’New Covenant’ and the ’New Law’

In Judaism there was a traditional view that the Torah was destined to lose its validity when the Messianic kingdom would begin. Combining this idea with the conviction that death and resurrection of Christ had ushered in that Messianic kingdom Paul came to the conclusion that the Torah was now suspended, the age of the Law had come to an end. Since on the one hand in the traditional view the observation of the Law lead to life and its transgression to death (in terms of individual salvation) while on the other hand experience taught that nobody was able to perfectly observe all the countless prescriptions, law-observance could not lead to life – only faith in Christ could bring salvation. God’s mercy had freed mankind from the yoke of the Law and from the resulting death.

This faith in Christ was the basis of a "New Covenant" which now had replaced the "Old Covenant". Those who still insisted in circumcision and Law-observance had not grasped the full salvation-historical meaning of the advent of Christ. Furthermore there was a continuity and even unity of the Old Covenant and the New. Those who wanted to accept only one ’half’ of this covenant (as the Jews did) were blind towards its actual meaning.

But on this basis a fundamental contradiction arose: (Marcel Simon) "The tangible sign of the covenant that God had established between himself and His people was the law, and the Bible codified that law, or rather, the Bible was the law." At the same time the Law should be abolished. Christians tried to solve this problem by recognising the validity of the Law for the time before the advent of Christ while denying it for now. Insofar there was a continuity between the two covenants, the Bible was of fundamental relevance for Christians. However the Pentateuch or even the whole Bible was considered as torah for good reason. So, (again Simon) "how could they claim the Bible as their own and yet at the same time empty it of so much of its content?" This question reflects "the whole problem of the relations between the two religions in a nutshell".

Paul saw the Law replaced by Christ. The Law had had its value in the past as a preparation and tutorial for the child and now had lost it for the adult man. If the observance of the Law was directed by its letter (Buchstabe), which was dead, what now had been revealed was the living spirit of it. Mere obedience to the dead letter was replaced by faith in the life-giving spirit and by this faith’s source, namely the divine grace.

In daily life however, this strict antinomism which denounced the Law generally as "dead letter" could not be applied. On that basis a practical religious life obviously could not be founded. Therefore a distinction was made in the early Church between those prescriptions which were abandoned through the Gospel, namely the laws of circumcision, Sabbath, fasting and sacrifice and the moral precepts which remained fully valid as expressions of the will of God, or, the natural law. About the Decalogue (the Ten Commandments), which was conceived as containing this natural law, Paul says "For when Gentiles who do not have the Law do instinctively the things of the Law, these, not having the Law, are a law to themselves, in that they show the work of the Law written in their hearts …" (Rom 2,14–15).

For the early Church Fathers it was clear that the original Israel had lost its legitimation by its rejection of Christ. God had transferred His favour to the gentiles, had abolished the old Law and replaced it by the new. The old Law had been characterised by the lex talionis ("eye for eye, tooth for tooth") wheras the new was one of love and peace.

The members of the New Covenant were justified by faith not by works (of Lawobservance). The circumcision of the flesh, i.e. the observance of all the prescriptions of the Law, had been replaced by the circumcision of the heart, i.e. conducting a life in faith and according to the spirit. What the spirit inspired was monotheism, faith in Christ and the natural, moral law, as codified in the Decalogue.

The problem of the indispensably persisting validity of the Hebrew Bible as fundament of the Christian religion was resolved by reinterpreting it as prehistory of the Christian Church. Israel ’after the flesh’ had been the ’shell’ which had contained the spiritual truth. This truth now had been freed by Christ and revealed to all the peoples. The shell itself had entirely lost its meaning to this New Israel. The ritual executions of the Old had symbolically prefigured that of the New: circumcision had prefigured baptism, sacrifices had prefigured prayers etc. Already Abraham had been justified by his faith, long before he underwent circumcision as a sign for his covenant with God. Even only centuries later the Torah had been revealed to Moses. Thus the New Covenant, based on faith, was in fact the original covenant of Abraham and Gods covenant with Israel had been a mere transitory state of the preexisting Church.

In their argument the early Christian apologists availed themselves of a quite popular notion of Graeco-Roman pagan philosophy, namely that of natural law. In the prelegalist era before Moses, the divinely approved norm of conduct was the natural law. It had been imperfectly embodied in the Mosaic legislation and men were capable of responding to it simply because of their natural endowment with the ability to recognise the natural law, or, God’s will. Christianity now had revealed this law explicitly to all mankind.

In crossing the boundaries of the people of Israel the Jesus-sect became an independent universal religion. The "covenantal nomism" of Israel was abandoned while the basis of this "covenantal nomism", namely the Pentateuch, the Written Torah was maintained. However one tries to interpret, or, justify this shift in the attitude towards the Torah in the process of the early Christian community detaching itself from Judaism, it can in my view only be conceived as a ’delegalisation’ of the revealed Torah of God.

Literature

SIMON, Marcel: Verus Israel. A Study of the Relations between Christians and Jews in the Roman Empire ad 135–425. London, 1986, repr. 1996 [= Verus Israel : Étude sur les relations entre chrétiens et juifs sous l$rsquo;Émpire Romain (135–425). Paris, 21964.]

RICHARDSON, Peter; WESTERHOLM, Stephen: Law in Religious Communities in the Roman Period. The Debate over Torah and Nomos in Post-Biblical Judaism and Early Christianity. (Studies in Christianity and Judaism / Études sur le christianisme et le judaïsme, vol. 4). Waterloo, Ontario, 1991.